The Paiter-Suruí people have a culture deeply rooted in their land: the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land (TISS), on the border of Rondônia and Mato Grosso in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon. Known as Paiterey Karah, this territory is home to rich biodiversity. However, increasing human encroachment has triggered socio-cultural and territorial challenges that now threaten the transmission of traditional wisdom.

The region’s wildlife includes several primate species—some now at risk of extinction due to deforestation and environmental degradation. Within their traditional memory, the Paiter-Suruí hold extensive knowledge about these animals, which are integral to their cultural heritage. This includes the 10 species of neotropical primates identified and named by the Paiter-Suruí, all native to their territory.

Of these 10 species, five appear on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List, a global benchmark for conservation status of fauna and flora. Among them, three—Ateles chamek, Chiropotes albinasus, and Pithecia mittermeieri—are considered extremely rare, according to Paiter tradition.

To bridge Indigenous expertise and scientific research, I conducted the study ‘Primates and the Paiter Surui People: Ethnobiology and Ethnoconservation in the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land of the Brazilian Amazon’, exploring the traditional ecological knowledge the Paiter-Suruí hold of non-human primates in their landscape. Developed during my master’s studies at the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, this is the first systematic ethnoprimatological study with the Paiter-Suruí.

Ethnoprimatology

Ethnoprimatology studies the intersections between humans and non-human primates. In this field, the Paiter-Suruí have developed a complex traditional knowledge system relating to the primate species in their territory.

Because it is inherently interdisciplinary, ethnoprimatology connects biology and anthropology, allowing a deeper analysis of how human and primate lives intertwine—both ecologically and culturally.

My research used an ethnoprimatological approach grounded in qualitative methodology, drawing on key practices from biological and cultural anthropology.

The study

This research aimed to document the breadth of Paiter-Suruí knowledge about the primates within the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land, examining both the cultural and ecological significance of these animals, as well as their uses—for food, handicrafts, traditional medicine, and timekeeping based on animal vocalizations.

Using an interdisciplinary approach, I holistically examined the biological, ecological, and socio-cultural factors shaping the human-primate relationship in this region.

The study took place in 2021 and 2022, with fieldwork in six communities across TISS. Qualitative methodologies guided the research, which drew on both an ethnographic literature review and a survey of ethnoprimatological research.

For data collection, I used several techniques: free listing, collective semi-structured interviews, participant observation—immersing myself in daily community life for deeper understanding—and audiovisual recordings.

Interviews included community members aged 20 to 80, with special attention to elders, who are the main custodians of traditional primate knowledge. However, women and young hunters were also included to enrich the information gathered.

Through the free list technique, which asks participants for open-ended answers without restrictions, I identified 10 primate species recognized and named by the Paiter-Suruí.

The primates of the territory

Among the 10 primate species documented in the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land, three are traditionally used as food, while four have special symbolic importance, woven into key cultural, ecological, and mythological aspects of the Paiter cosmology.

An illustrative case is the red-necked night monkey—called Yaah in Paiter. Elders say this species is excluded from the community’s typical primate classifications and instead regarded as an omen. Hearing its call or unexpectedly seeing one signals the approach of external enemies or impending death in the community.

While exploring these cultural ties to the region’s primates, I also observed the practice of rearing infant animals, especially among girls. Species such as Alouatta puruensis (howler monkey), Saimiri ustus (squirrel monkey), and Mico nigriceps (black-headed marmoset) are commonly involved.

In Paiter-Suruí society, adolescent girls often care for offspring of monkeys hunted by the community, as well as other small animals outside their typical diet. Encouraged by parents, this tradition is a vehicle for socialization and passing down valued skills. By raising young animals, girls develop emotion, empathy, nurturing skills, and hands-on experience seen as foundational for motherhood in Paiter tradition.

Beyond developing caretaking abilities, these interactions strengthen symbolic and emotional connections with local wildlife—especially primates—reinforcing ideals of belonging, reciprocity, and respect for nature. These practices demonstrate the interplay among social learning, interspecies relations, and ecological wisdom passed down through generations.

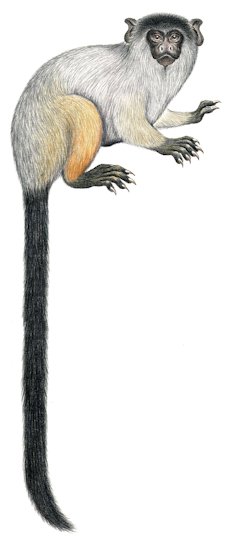

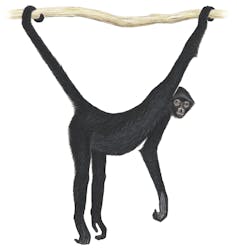

Community members also reported declining populations of certain primate species, including two—Yaah (Aotus nigriceps) and Arimẽ-Iter (Ateles chamek)—that hold special cultural significance. The latter became a central focus of my research.

The endangered Arimẽ-Iter

The black-faced spider monkey (Ateles chamek), or Arimẽ-Iter to the Paiter, is classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List. Its sacred status and diverse roles led me to propose it as a ‘Cultural Key Species’ for the Paiter-Suruí.

In various Indigenous communities, certain biological species are of exceptional cultural importance and are called Cultural Key Species. Defined by their significant role, many uses and deep integration in community life, these species embody the interdependence between people and their environment.

For the Paiter-Suruí, the black-faced spider monkey (Ateles chamek) stands out for its multiple uses and appears to meet the criteria of a Cultural Key Species.

Based on field observations, I cataloged five uses the Paiter-Suruí associate with this species:

· Food: The meat of Ateles chamek (called Sobag) is an important protein source in the Paiter-Suruí diet.

· Traditional dishes: Its meat is used in cultural recipes, often with Mamé—a flatbread made from corn flour. This practice passes down culinary knowledge and highlights the species’ nutritional, medicinal, and symbolic value in the community.

· Handicrafts: Spider monkey teeth are made into body ornaments (Sogap Arimẽ Ikaáp)—such as necklaces and bracelets—which reflect status or ceremonial participation and reinforce ties between people and local fauna.

· Medicine: The animal’s lard is traditionally applied to wounds (Ikawah), part of the community’s oral ethnopharmacological knowledge passed down by elders and healers.

· Caretaking: When infants are orphaned through hunting, adolescent girls may raise young spider monkeys. This reinforces learning about caretaking and builds affectionate, reciprocal ties between people and primates (Yatĩga), reflecting broader values of coexistence with nature.

Together with ancestral stewardship of spider monkey habitats, these uses highlight the species’ role as essential for cultural preservation and identity among the Paiter-Suruí.

Territorial and environmental management plan

Facing growing socio-environmental challenges, the Paiter have created internal policies for territorial management, grassroots political organization, and culturally centered development—all to protect their culture and traditional knowledge.

This laid the foundation for the Territorial and Environmental Management Plan (PGTA) for the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Land, launched in 2000 as a comprehensive framework guiding conservation, resource management, and recognition of cultural practices.

In my research, I examine TISS land management practices, focusing on the protection of primates as essential to ecological preservation. These animals are vital both for maintaining natural balance and for the cultural continuity of the territory.

Of the 10 primate species recognized by the Paiter, five now qualify as threatened under the IUCN Red List. However, the PGTA currently lacks targeted conservation measures for these at-risk populations. My findings suggest the management plan could serve as a platform to protect local primates.

Ultimately, enacting effective conservation efforts for these ethno-species is critical to the coexistence of the region’s biodiversity and the traditional knowledge of the Paiter-Suruí.